I sometimes lay my clothes out the night before, but there is a flaw in this system. How can I possibly know who I will be the next morning? Last night, for example, I placed a grey sweater on the chair. Grey seemed appropriate: calm and neutral. But in the morning the sky was already grey, the buildings were grey, and even the river looked grey. So, instead I reached for the sky-blue sweater. Immediately, the day felt different. Not brighter exactly, but different. Just before stepping out of the apartment, I hesitated again and added a camel scarf. Grey. Blue. Camel. Three small decisions. We often think of clothing as something we choose for practical reasons. What we are doing. Where we are going. Who we might meet. But it does something more subtle. Blue slows the breath. Yellow improves the mood. Green suggests rest and balance. Red energizes. Even people who primarily wear only neutrals are still choosing a tone or texture. A charcoal black feels different from a soft beige. A crisp white shirt feels different than a pale grey t-shirt. Some people call this “dopamine dressing” – the idea that certain colours or textures lift our mood. This makes the ritual of laying out clothes the night before slightly mysterious. We are trying to predict a mood that does not yet exist. We may believe we are dressing for the world, but often we are dressing for our inner weather. We have a form of conversation with ourselves, or between the weather outside and the weather within. As Cyndi Lauper sang in 1986: “I see your true colours Perhaps the trick is not for me to lay out my clothes too strictly. Leave a little room for improvisation. After all, moods change. Sometimes, the day only needs one small adjustment to show my true colours. True colours are beautiful, like a rainbow. Additional reading: Making my peace … with choosing what colour to wear Can’t see the whole article? Want to view the original article? Want to view more articles? Go to Martina’s Substack: The Stories in You and Me More Paris articles are in my Paris website The Paris Residences of James Joyce You're currently a free subscriber to The Stories in You and Me . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

latestpets

Monday, 9 March 2026

It was a grey day until I wore blue: a flaw in the system

Sunday, 8 March 2026

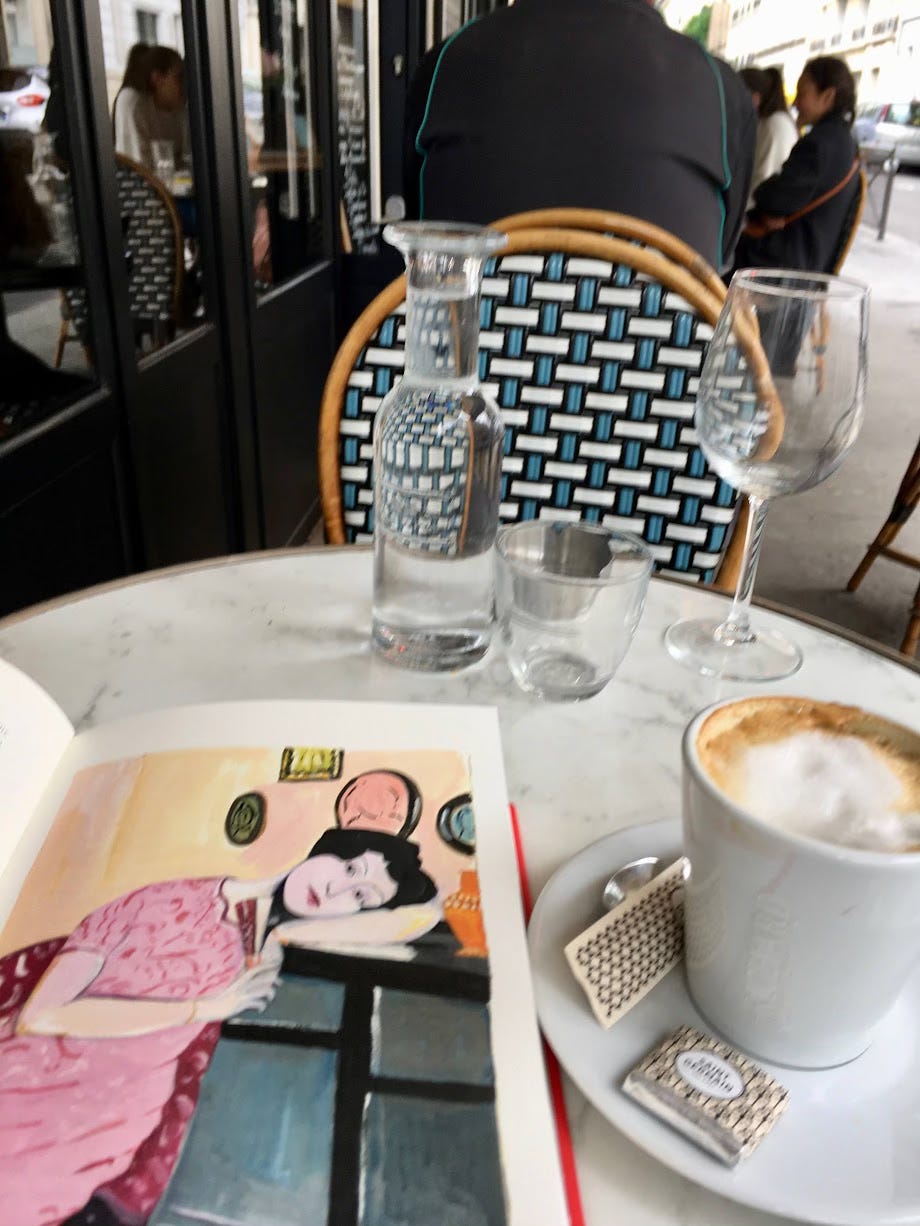

Low tables, high thoughts

My landlord asked me a practical question: “Would you like a table basse in the apartment?” In French, table basse simply means low table. It is a beautifully literal phrase. A table … that is low. I said yes. Two days later, he appeared again, this time with another offer: “Perhaps you would also like a second table basse?” At this point, I began to suspect that somewhere in the depths of Paris he possesses a quiet warehouse of low tables waiting for homes. The conversation made me think about low tables. In English we do sometimes say low table, but mostly we say coffee table. Once I noticed that phrase, it became oddly mysterious to me. Why coffee? It originated in the twentieth century. As living rooms became more informal, people began sitting on lower sofas and chairs rather than upright Victorian furniture. A lower table was a better fit for the new posture of relaxation. These tables were meant to hold the small things of conversations: cups, ashtrays, newspapers, perhaps a plate of biscuits, and coffee during conversation. So, the table was named for what happened around it. Which is a lovely idea when you think about it. And then came the coffee table book. These books are large and glossy, with lots of photographs. They sit on the table waiting for someone to open them while visiting. The phrase itself became popular in the 1960s when publishers realized that beautiful, over-sized books, on art, travel, photography, architecture, and so on, were perfect objects to leave on the living room table. Beautiful books that start conversations. Which is slightly ironic, because people sometimes say a coffee table book is a book without a story, just photos. But that isn’t really true. There are plenty of stories: one, or more, in every photo. As for my apartment, I now suspect that if I stay here long enough my landlord may eventually offer me an entire family of tables basses: a little parliament of low tables gathered in the living room. If that happens, I will of course need more coffee table books. After all, every table deserves a story. Can’t see the whole article? Want to view the original article? Want to view more articles? Go to Martina’s Substack: The Stories in You and Me More Paris articles are in my Paris website The Paris Residences of James Joyce You're currently a free subscriber to The Stories in You and Me . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. © 2026 MARTINA NICOLLS |

It was a grey day until I wore blue: a flaw in the system

… and then I wore camel instead … ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏...

-

thealchemistspottery posted: " "I shall pass through this world but once.If therefore, there be any kindness I can sho...

-

Stimulate the body to calm the mind Cross Fit for the Mind The Newsletter that Changes the Minds of High Performers If overstimulation is th...

-

petrini1 posted: " For Week 7, the theme of genealogist Amy Johnson Crow...