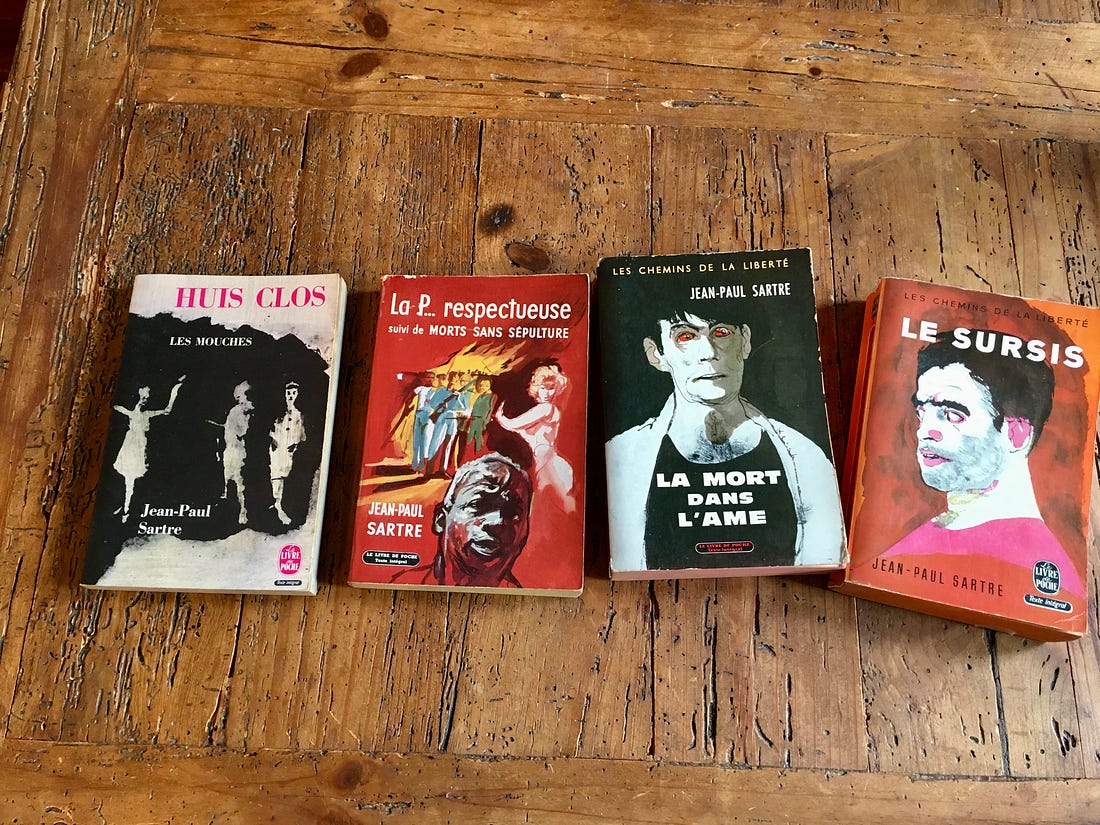

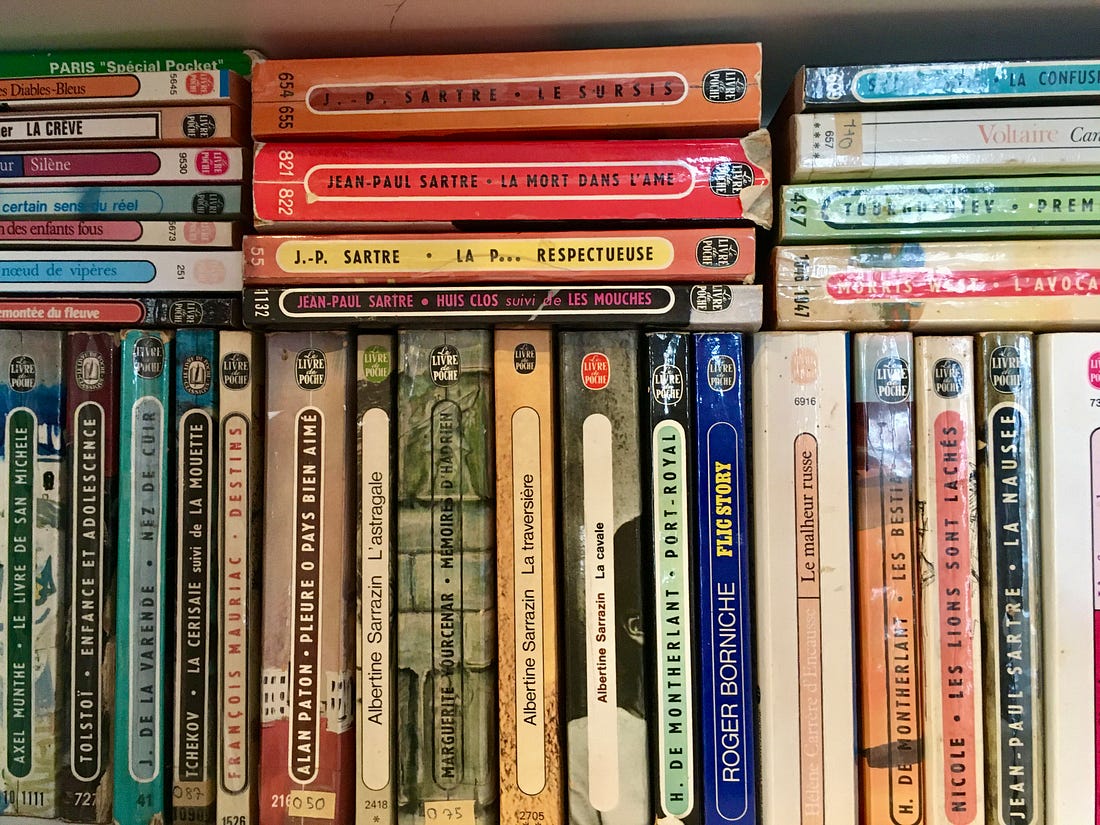

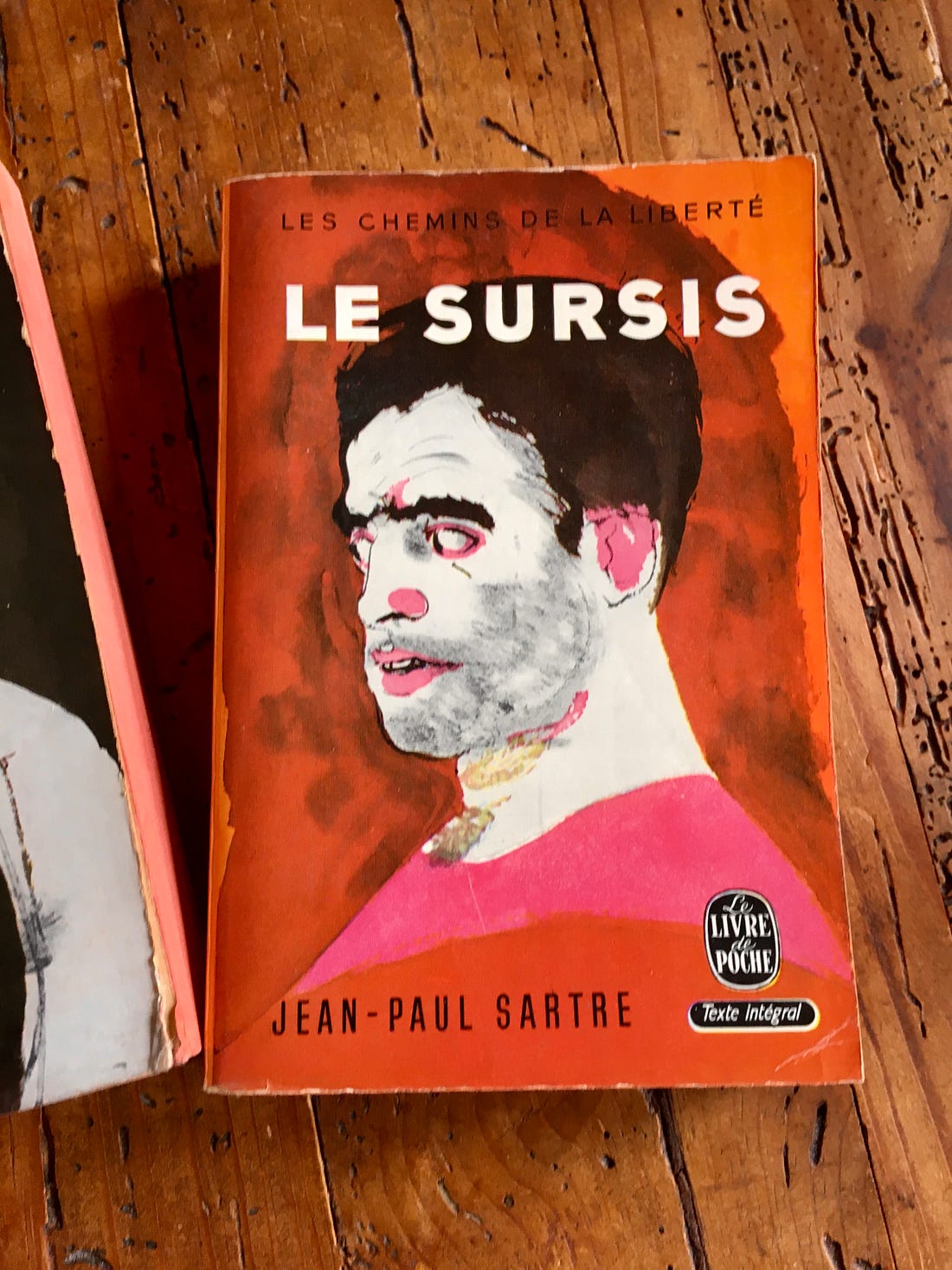

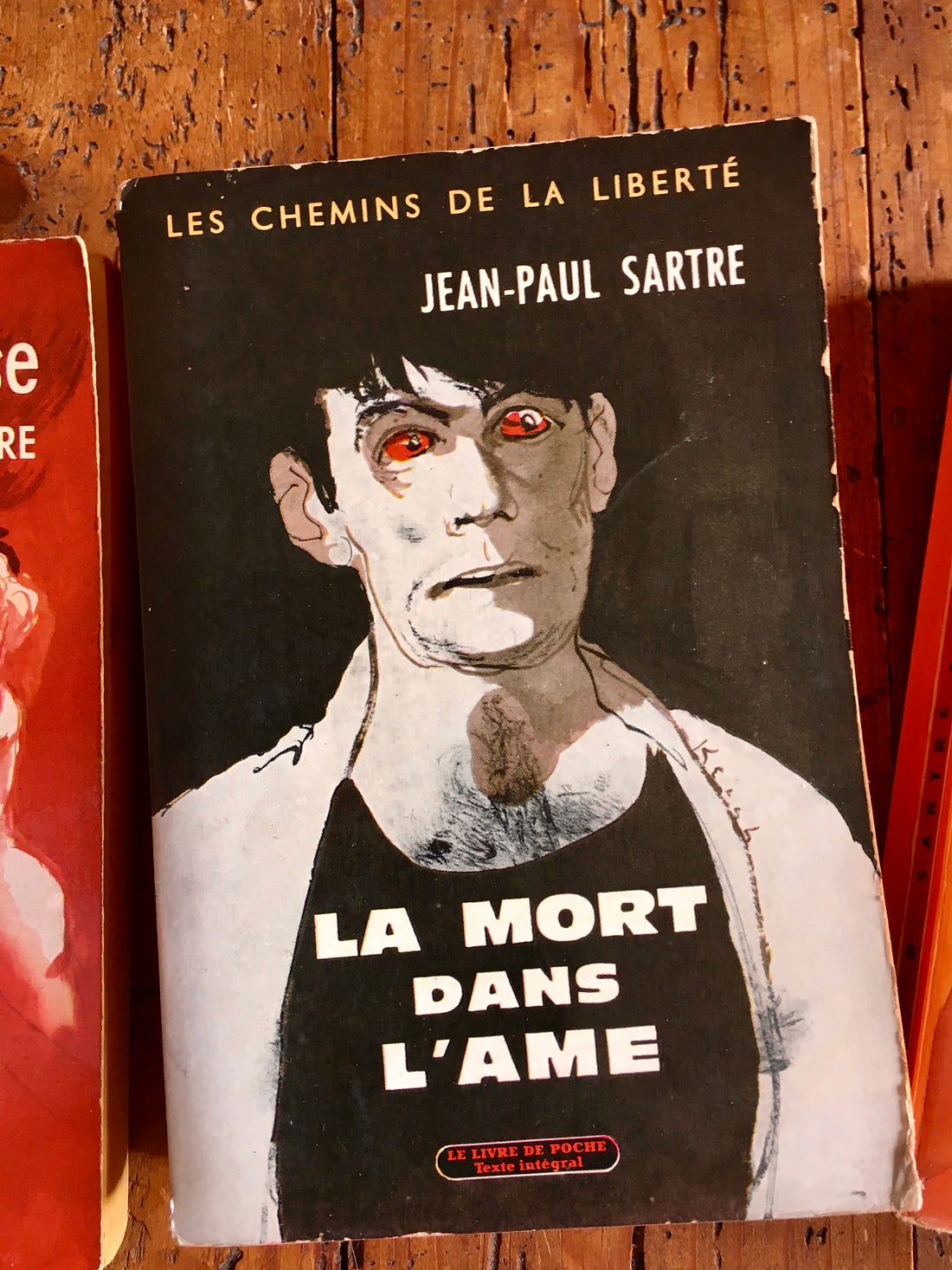

Since the first Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded in 1901, France is the home of the most literature winners than any other country (broadly speaking: French or Francophone‐language authors with French nationality or strong ties to French language and culture). There have been 16 French‐language and national French Nobel laureates noted for either a single book or a body of work. There are caveats of course. Bias toward European literature and translated works into European languages has been an issue, though the criteria have changed over the past 100 years. The quantity of the Nobel prize winners is not the only measure, or even the best measure, of literary worth. Many great writers never win, and many important literature works are under‐recognized because of language, colonialism, lack of translation, etc. Also, while France does lead in the number of laureates, that doesn’t necessarily translate into global readership. Many winners are known only in academic or intellectual circles rather than being widely popular. Patterns emerge from the writing of the 16 French Nobel Prize winners that are not universal, although they indicate strong tendencies. Their writing is poetic, through verse as well as poetic expression in prose, which is described as the art of conveying emotions through imaginative language and literary devices such as metaphor, simile, and rhythm. Many French laureates are engaged with personal or collective memory and history, often with a colonial, wartime, occupation, or existential dimension. Ethical, moral, spiritual, and philosophical works tend to play a major role in French literature. Human dignity, social injustice, identity, class, idealism, colonialism, and the like, are recurring themes, categorized under social critique and humanism. The complex history of France with its colonialism, wars, and wartime occupation, provides material for morally complex narratives and questions of identity and justice. Although rooted in France geographically, culturally, and historically, their works have universal resonance. France, especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was a global hub for literature, philosophy, and the arts. French was the lingua franca of educated Europe, and Paris was a magnet for creatives and intellectuals which birthed a rich culture of literary competition and innovation. France places authors on a pedestal, encouraging literary criticism and review, scholarly institutions, awards, salons, and publishers who invest in literary ambition. France’s literary culture does not strictly separate literature from philosophy and therefore ideas and style are often integrated. French as a major European language has been well translated and well read. Authors writing in French reach wider audiences and are more visible to the Nobel committee. What can writers learn from this “French success” pattern? 1. Engage honestly with personal or collective memory, especially moments of trauma, identity, and transition, to connect readers across cultures. Don’t shy away from reconciling the personal and the historical. 2. Be courageous and honest while challenging injustice, class, gender, colonial legacies, or moral complexities. 3. Pose intellectually weighty questions about ethics, existence, and society, to stimulate thinking as well as emotional responses. 4. Write quality works, of language style, structure, tone, and voice, rather than solely “content.” 5. Experiment with language. 6. Ground writing in the local culture or linguistic particularities while aiming for universal human themes. 7. Persist, reflect, and evolve your unique writing identity, within society and culture, to express an authentic voice. *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** The 16 French Nobel Prize in Literature winners are: 1901: Sully Prudhomme - for his poetic composition “which gives evidence of lofty idealism, artistic perfection and a rare combination of the qualities of both heart and intellect.” 1904: Frédéric Mistral – for “poetic production reflecting the native spirit of his people (Occitan language) and for philological work.”| 1915: Romain Rolland – for “lofty idealism … and the sympathy and love of truth with which he has described different types of human beings.” 1921: Anatole France – for “brilliant literary achievements, characterized … by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament.” 1927: Henri Bergson – for his “rich and vitalizing ideas and the brilliant skill with which they have been presented.” 1937: Roger Martin du Gard – for the “artistic integrity and the depth of his novel cycle The Thibaults, among other works. 1947: André Gide – for his “comprehensive and artistically significant writing, which, with clear‐insight, expresses human problems in contemporary moral terms.” 1952: François Mauriac – for the “deep spiritual insight and the artistic intensity with which he has in his novels penetrated the drama of human life.” 1957: Albert Camus – for his “important literary production, which with clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in our times.” 1960: Saint‐John Perse – for the “exalted lyrical writing which in a visionary figure gives poetic expression to the whole being of man.” 1964: Jean‐Paul Sartre – for “his work which, rich in ideas and filled with the spirit of freedom and the quest for truth, has exerted a far-reaching influence on our age.” (He declined the prize.) 1969: Samuel Beckett – Irish author living in France, for “his plays, novels and essays which introduced a profoundly different narrative impulse.” 1985: Claude Simon – for his “novel‐writing which combines the intensive and poetic qualities of language with the perceptiveness of the realist tradition.” 2008: J. M. G. Le Clézio – for “new departures, poetic adventure and sensual ecstasy, explorer of a humanity beyond and below the reigning civilization.” 2014: Patrick Modiano – for “the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation.” 2022: Annie Ernaux – for “the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.” Can’t see the whole article? Want to view the original article? Want to view more articles? Go to Martina’s Substack: The Stories in You and Me More Paris articles are in my Paris website The Paris Residences of James Joyce Rainy Day Healing - gaining ground in life You're currently a free subscriber to The Stories in You and Me . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Thursday, 2 October 2025

Why France is the home of the most Nobel prizes in literature

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Freedom, fire, and fate: 3 horse songs for the Lunar Year of the Red Fire Horse

… 2026 … a year of movement, courage, instinct, passion, and sudden turns of fate … ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

thealchemistspottery posted: " "I shall pass through this world but once.If therefore, there be any kindness I can sho...

-

Stimulate the body to calm the mind Cross Fit for the Mind The Newsletter that Changes the Minds of High Performers If overstimulation is th...

No comments:

Post a Comment