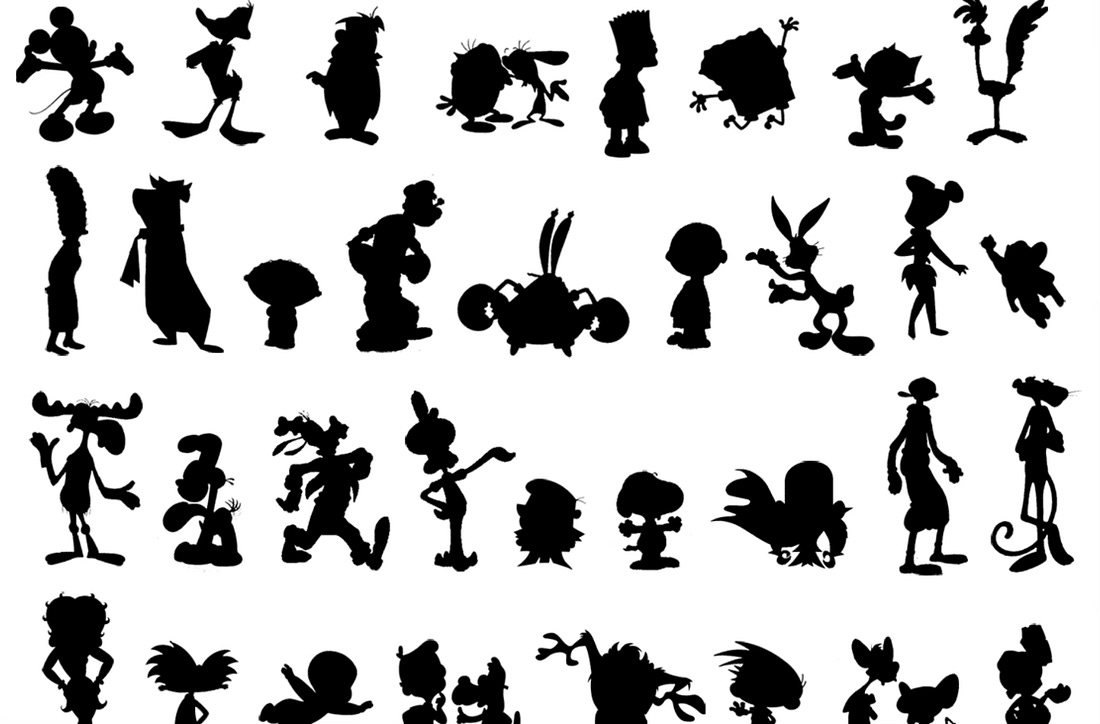

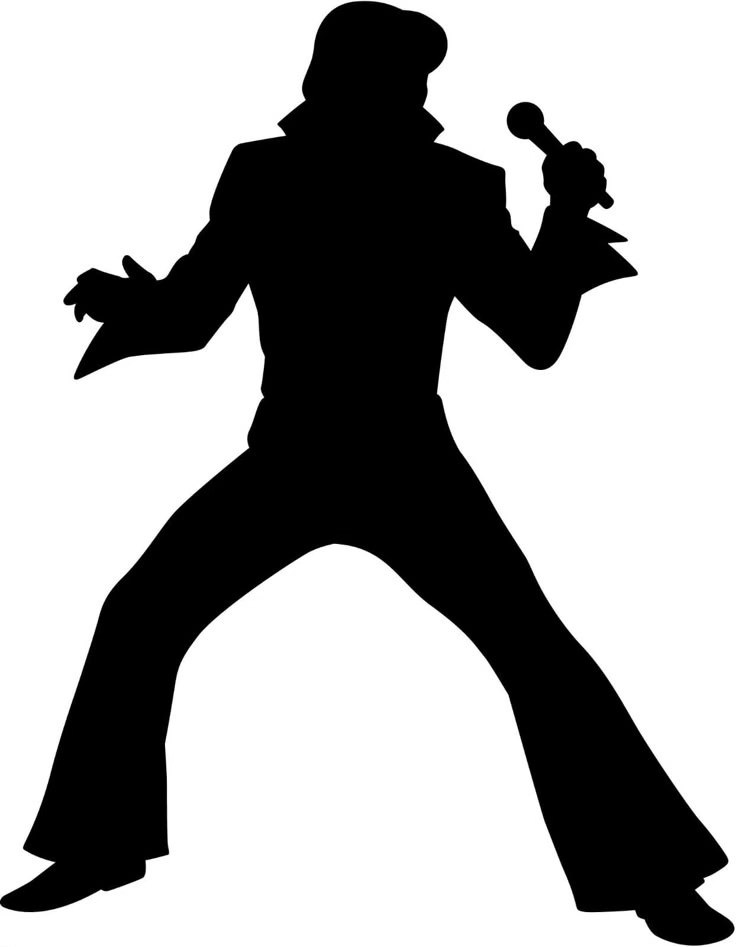

Silhouette Power: why great characters are recognizable immediately… before we see a face, we see a shape, a shadow, a silhouette …Before we know who someone is, we often know what their characteristics are – and whether we are looking at a historical person or a literary character. This is the power of the silhouette. Long before the brain looks for detail, it searches for a shape and the recognition of a pattern, such as a posture, movement, or outline — to know friend from foe, leader from follower, protector from prey. A silhouette strips a person down to their very essence. It removes distraction. It invites the imagination to complete the picture. It activates memory, emotion, and myth. This is why silhouettes are dramatic. Some historical people become instantly recognizable through their form, not their face. Napoleon — the bicorne hat, hand tucked into his coat, and a compact frame. His silhouetted stance suggests ambition, authority, and power. Alfred Hitchcock — rounded belly, receded chin, and full suit. A silhouette that reveals the architect of suspense and unease. Winston Churchill — bowler hat, stocky shape, and cigar angled forward. His outline embodies defiance and resistance. Jane Goodall — slim figure, ponytail, and binoculars. A human silhouette of curiosity and intense observation of the chimpanzees she studied. In each case, the silhouette reveals the person’s biography. It tells us how someone moves through the world. It signals temperament before face and voice. We do not merely recognize the person through the silhouette; we feel them, we know of them, we know their psychology through their hat, hair, object, or stance. Cinema understands silhouette instinctively. Directors often introduce important characters in shadow because the outline is more mythic than the face. Faces belong to individuals, but silhouettes belong to archetypes. Batman – cowl with pointed ears, cape falling into a jagged wing, and broad shoulders tapering into a still, strong figure. Batman’s silhouette is engineered myth. Even without detail, he is instantly readable as a nocturnal rescuer, half-human and half-symbolic. The cape enlarges. The ears depict something animalistic. His silhouette doesn’t just identify him — it warns his foes while simultaneously heartening those in need. Mary Poppins – hat perched neatly on her coiffed hair, high-collared coat, a large carpet bag, and a curved umbrella. Mary Poppins’ silhouette is order and discipline, but also magic and delight. Proper but floating. Her outline informs us that she has arrived from somewhere else, part governess and part apparition. Film and photography love a strong silhouette because it can hold an entire narrative inside a totally blackened shape: a man with a cane (like Charlie Chaplin) or a woman with a “space buns” hairstyle that covers her ears (like Princess Leia). Literature too uses silhouette to make a character memorable by the way the character occupies space, the objects they carry, or the gestures that become their signature. Some literary silhouettes are unforgettable. Sherlock Holmes – deerstalker hat, long coat, pipe, and angular stillness. Even on the page, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle built Sherlock Holmes from vertical lines, spires, and smoke. His silhouette is intellect and the relentless search for the truth made visible. Miss Havisham – stiff figure in a wedding dress, unmoving in a dark room. Charles Dickens constructed her silhouette in Great Expectations as time stalled. A human clock that stopped. Jay Gatsby – a solitary figure stretching his arms toward a green light. That single posture of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby becomes a silhouette where mystery and yearning is given shape. The Little Prince – the small body, scarf lifting behind him. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s outline shows the boy’s adventures to far off planets, but also his fragility. Dracula – cape, height, starkness, and unnatural verticality. Bram Stoker’s silhouette invades rooms before his personality needs to speak. A mythic silhouette becomes symbolic. At a certain point, silhouettes detach from individuals altogether and enter the world of imagination: a caped figure on a rooftop (like Batman), a woman floating with an umbrella (like Mary Poppins), or a lone child on a small planet (like the Little Prince). A mythic silhouette becomes an entire emotional world: justice, wonder, innocence, danger, hope. And myth is always visual before it is verbal. The silhouette forces a structural question every storyteller eventually faces: “If my character were seen from afar … what posture do they habitually inhabit?” Silhouette shapes how others respond to a character. It shapes power dynamics. It shapes memory. People experience fear, or love, or trust, or happiness from a silhouette. Their outline is often their first language, before words, and often their truest self. And if you are creating a character, ask yourself: What is the shadow they cast on the wall of the story? What would a child draw after seeing them once? Because long after dialogue is forgotten, after plot fades, after faces blur … the silhouette remains. Can’t see the whole article? Want to view the original article? Want to view more articles? Go to Martina’s Substack: The Stories in You and Me More Paris articles are in my Paris website The Paris Residences of James Joyce You're currently a free subscriber to The Stories in You and Me . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Sunday, 25 January 2026

Silhouette Power: why great characters are recognizable immediately

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Silhouette Power: why great characters are recognizable immediately

… before we see a face, we see a shape, a shadow, a silhouette … ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

thealchemistspottery posted: " "I shall pass through this world but once.If therefore, there be any kindness I can sho...

-

Stimulate the body to calm the mind Cross Fit for the Mind The Newsletter that Changes the Minds of High Performers If overstimulation is th...

No comments:

Post a Comment